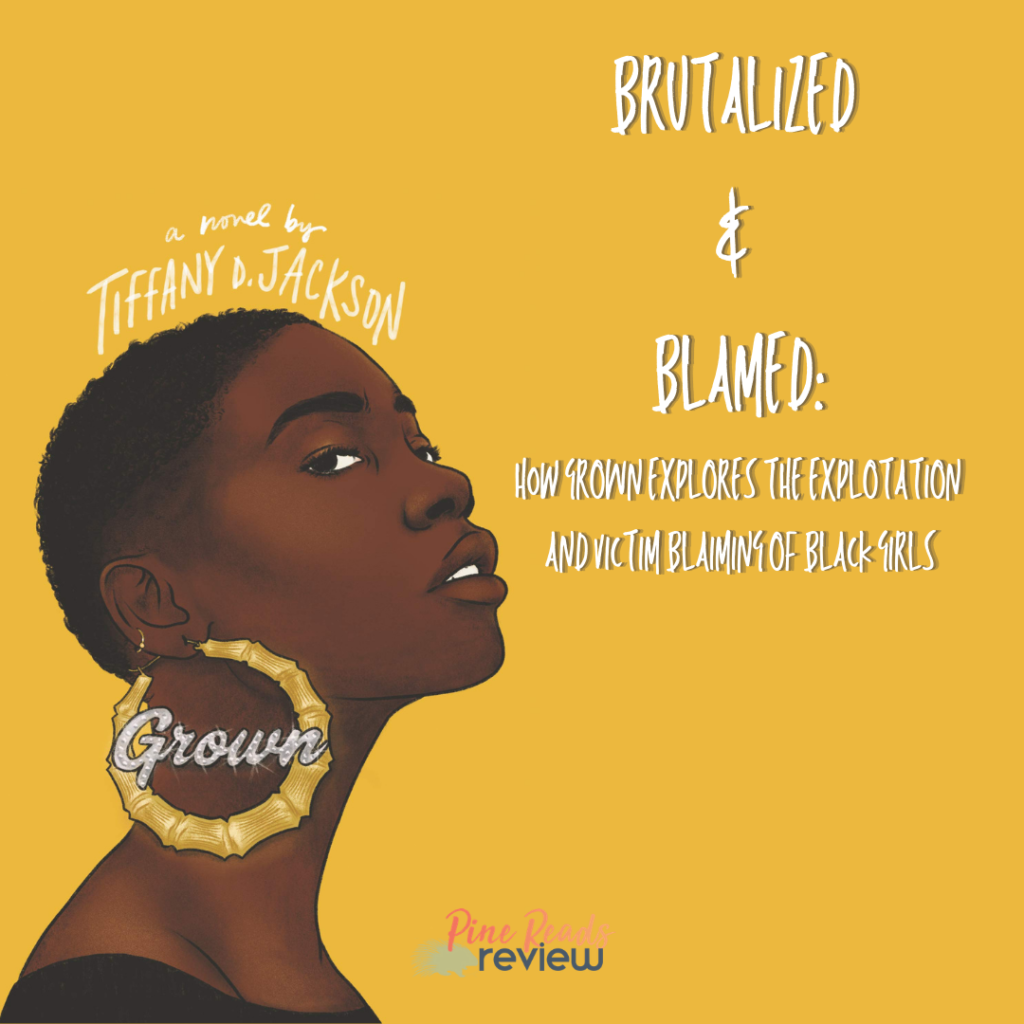

Tiffany D. Jackson has done it again. Her newest novel, Grown, released only a few months ago from Katherine Tegen Books and I have been dying to pick it up ever since. I read Jackson’s previous young adult thriller Monday’s Not Coming a couple years ago and I think about that story and those characters on a daily basis—and no surprise, Grown has had the same effect on me. The story follows aspiring singer and competitive swimmer Enchanted Jones as she tries to showcase her talent and prove to her family that singing is a passion worth chasing. Then everything changes when Enchanted meets Korey Fields, a legendary recording artist who takes her under his wing. It seems like Enchanted’s dreams are finally coming true, until the man who promised her the world preys on her insecurities and controls her every move. Things take an even darker turn when Korey is found dead and everyone—the police and Korey’s fans included—think that Enchanted is the one who did it.

I had a very visceral response to the events of this novel, not only because Korey Fields manipulates and abuses Enchanted, but because, despite having gone to hell and back, she is still painted as the villain while her rapist escapes relatively unscathed. While reading, I felt a constant pang in my chest, knots in my stomach, and was so uneasy that I couldn’t sleep. Instead, I just kept thinking about how very real and tragic this story is. Although it’s fictionalized, Grown is another one of Jackson’s ‘pulled from the headlines’ stories, emphasizing the ways that victims are blamed and silenced—simply because no one will believe them. Unfortunately, Enchanted’s story is all too real. I knew instantaneously who, at least in part, inspired the character of Korey. And while I refuse to say his name, I appreciate how Jackson calls him, and all others like him, out for their monstrous acts of abuse, violence, and manipulation.

Much of the novel explores the intersections of power dynamics and abuse with age, gender, and race. Grown exhibits the twisted way that adult men can infiltrate young girls’ lives and cause lifelong trauma through detrimental one-sided “relationships” that really should never have even existed in the first place. As Jackson writes, “No grown man can have a relationship with a child.” The title itself underscores the ways that young brown and Black girls are forced into maturity mainly because they look older. More than that, to be labeled as “grown” has always been a manner in which adults dismiss the ways that children suffer. I myself can remember being told something like ‘you look grown so act like it’ as a kid—but just because someone says it, doesn’t mean that it’s true. Among the many, many powerful lines, “Not looking their age doesn’t change their age,” is one of the most poignant. I also deeply appreciate a similar sentiment in, “No child should ever take the blame for a man’s actions.” I’ve mentioned this in a previous blog, but I was a girl whose body developed “too fast” and because of this many people assumed I was “fast.” This is another aspect that Jackson discusses so pointedly: the sexualization of young girls. Despite how a girl grows up—in a two-parent household, with their grandparent(s), alone or with a single parent, poor or affluent—Jackson makes it known that this kind of exploitation can happen to anyone, and that it’s so goddamn important to believe survivors.

The novel opens with Enchanted in a state of shock and covered in blood; suddenly, we are thrust back to the beginning, before Korey and all the terror he brings with him. Over the course of all 384 pages, he abuses his power and money, commits rape, assault, stalking, and is responsible for a leaked sex tape (which is actually child pornography). Despite all this, some of Korey’s fans still vilify Enchanted for things that were truly out of her control—completely invalidating her trauma and Korey’s unequivocal culpability. Therefore, the most heartbreaking aspect of Grown is Enchanted’s story arc. As a Black teen girl, she already has societal expectations and systemic prejudice working against her. Then there’s the added pressure to ‘stand out’ as an aspiring singer and stress from her parent’s financial issues. And that’s before her kidnapping, rape, and abuse are taken into account. At no point does Enchanted Jones just get to be a “regular” teenager—this is the driving force of the novel. With a deft hand, Jackson points out how our society looks at Black girls and boys differently; how, because of this, they are often the ones who are forced to endure the most.

PRR Writer, Jackie Balbastro