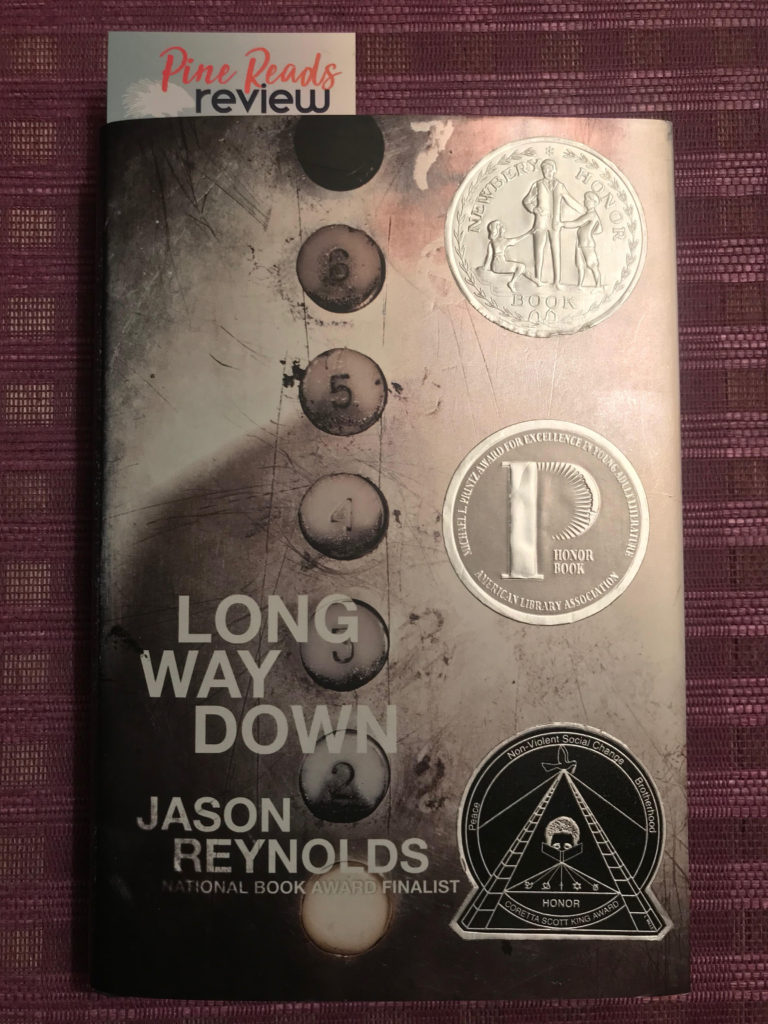

Long Way Down: A Window to Social Awareness

Author: Jason Reynolds

I first read Jason Reynold’s novel in verse Long Way Down a few months ago for one of my classes. What struck me the most then was the ending. Just two words that if I share here won’t make much sense nor make an impact, so I won’t, which is my way of encouraging you to read this raw, memorable book about Will, a 15-year-old African American boy who must decide what to do about his brother Shawn’s murder: will he follow “the rules” and get revenge or will he break the destructive cycle? I remember sitting down next to a classmate right after finishing the novel and saying, “Oh my god – that ending.” She answered, “I know, right? It gave me goosebumps.” Now, the punch-in-the-gut ending still gives the chills, but my attention has shifted to the beginning, or rather, the dedication page. It reads:

“For all the young brothers and sisters in detention centers around the country, the ones I’ve seen, and the ones I haven’t. You are loved.”

I must have glossed over the dedication page upon first reading Long Way Down, but on my second read-through, those two sentences stood out to me and seemed to click in my mind. I am currently taking a course about prison writing but more specifically about the American prison system, the national crisis of mass incarceration, and the overwhelmingly and disproportionately high number of incarcerated African Americans compared to other races. With these topics fresh in my memory, Reynold’s opening words caught my attention since they seem to make reference to the mass incarceration and criminalization of blacks in America or, as Michelle Alexander puts it, “the new Jim Crow.”

Through “the rules” – no crying, no snitching, get revenge – Shawn’s murder, and Will’s tough decision on whether to follow the rules, Reynolds shows the tragic impact that the criminalization of blacks has had on this fictional yet very real community. Violence and imprisonment have been normalized in these characters’ lives. When Shawn turned eighteen, his mother “began to pray that he wouldn’t go to jail… that he wouldn’t die,” and when he was shot, Will says it was “not surprising.” Ravished by lack of opportunity, systemic racism, and the war on drugs – a movement of political reform historically targeted at African Americans – impoverished, minority communities, such as Will’s, are plunged into a cycle of violence and serving time, into a cycle of following “the rules.”

I feel rather embarrassed for not making this connection during my first read-through of the novel or rather for not knowing enough about mass incarceration and how it directly and immensely affects black Americans. However, I am excited to continue learning about this subject and to read more YA literature that explores it. Through his short, potent free verse, Reynolds navigates these issues gracefully and with grit. Making an impact on those who can relate to Will’s predicament, have seen it in their communities or have lived it first hand, as well as to those who have never come close to experiencing it.

For eye-opening reads on mass incarceration in the United States, the deliberate criminalization of African Americans, and how the war on drugs and tough-on-crime political movements have targeted and devastated the black community, please take a look at Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow and Ta-Nehisi Coates’ article “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration.”

PRR Writer, Alessandra De Zubeldia

WHAT DO YOU THINK? READ IT YOURSELF AND SEE!